Cholesterol Found to Play Key Role in Protecting the Blood-Brain Barrier

The brain is protected from harmful substances in the blood by a tightly regulated layer of cells called the blood-brain barrier. This barrier is formed by brain endothelial cells, which are connected by proteins known as tight junctions. These junctions seal the spaces between cells, preventing toxic compounds and inflammation-causing molecules from entering the brain. Cholesterol is a key component of cell membranes, and changes in cholesterol levels can alter the structure and function of membrane proteins.

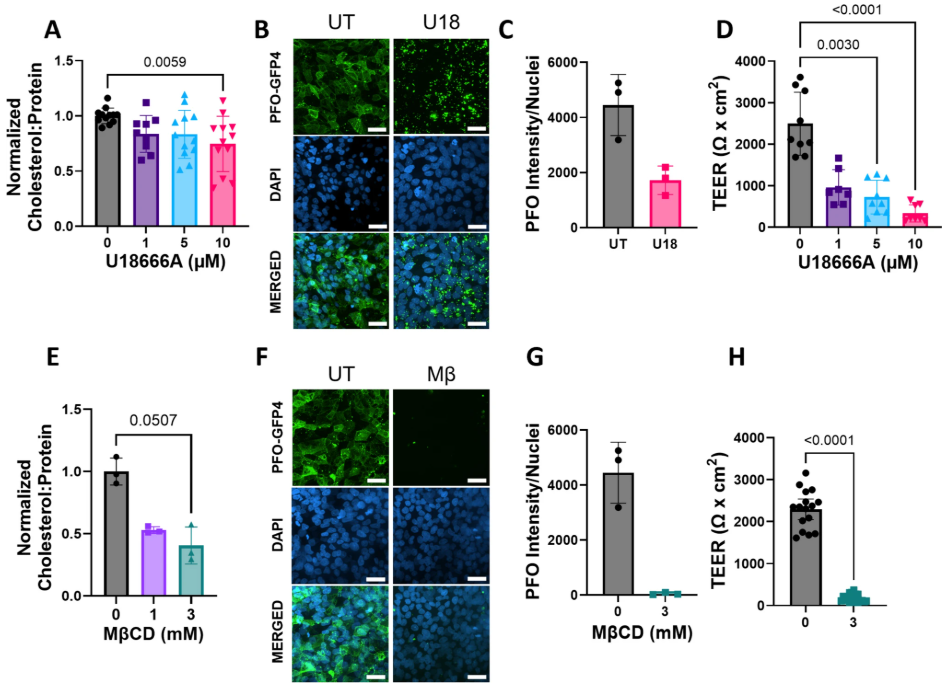

A new study led by Fischell Department of Bioengineering (BIOE) Professor Alisa Clyne and first author, BIOE MD-PhD student Bilal Moiz, investigates how cholesterol supports the structure and function of the proteins that form the blood-brain barrier. The research, published in Annals of Biomedical Engineering, shows that reducing cholesterol in brain endothelial cells weakens the barrier and increases permeability to smaller molecules.

In the study, Clyne and her lab tested two models of cholesterol depletion. In the first, they used a compound called methyl-β cyclodextrin to remove cholesterol directly from cell membranes. In the second, they inhibited a protein called NPC1, which normally moves cholesterol inside cells. NPC1 dysfunction occurs in Niemann-Pick Disease Type C1, a rare disorder where cholesterol becomes trapped in certain compartments and is unavailable to the rest of the cell. These findings provide new insight into Niemann-Pick Disease Type C1. They suggest that the blood-brain barrier in these patients may allow small toxic or inflammatory compounds to enter the brain, potentially contributing to long-term neuronal damage. The results also indicate that restoring barrier function could be a strategy to slow disease progression. At the same time, the research highlights an opportunity for drug delivery as small therapeutics may still cross the barrier, offering potential treatment options for Niemann-Pick Disease Type C1. “Decreased blood-brain barrier integrity is a hallmark of many neurodegenerative diseases,” Clyne said. “We wanted to know whether similar changes might also occur in rare metabolic disorders like Niemann-Pick Disease Type C1, especially given what we know about cholesterol and its role in cell membranes.”

As principal investigator of the Vascular Kinetics Lab, Clyne and her team specialize in connecting molecular-level changes to larger biological outcomes. By studying how cholesterol influences the function of endothelial cells, the team aims to uncover mechanisms that could guide therapies to protect or restore the blood-brain barrier in disease. The researchers also observed reduced levels of claudin-5, a tight junction protein critical for keeping small molecules out of the brain. Importantly, restoring cholesterol to the cells reversed the increased permeability, demonstrating that cholesterol directly supports tight junction function. Beyond rare genetic diseases, this work may aid scientists in understanding more common conditions. Mutations in NPC1 and reduced cholesterol levels later in life are both linked to Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting shared mechanisms in how cholesterol influences the blood-brain barrier. By showing how cholesterol supports tight junction structure and blood-brain barrier selectivity, this study brings researchers closer to understanding how metabolic disorders contribute to neurological damage and how the brain may be better protected in the future. Looking forward, Clyne and her team are exploring therapies that boost plasma membrane cholesterol in brain endothelial cells to strengthen the barrier and prevent neurodegeneration.

Related Articles: January 16, 2026 Prev |

|