Multi-institutional Research Team Documents Quantum Melting of Wigner Crystals

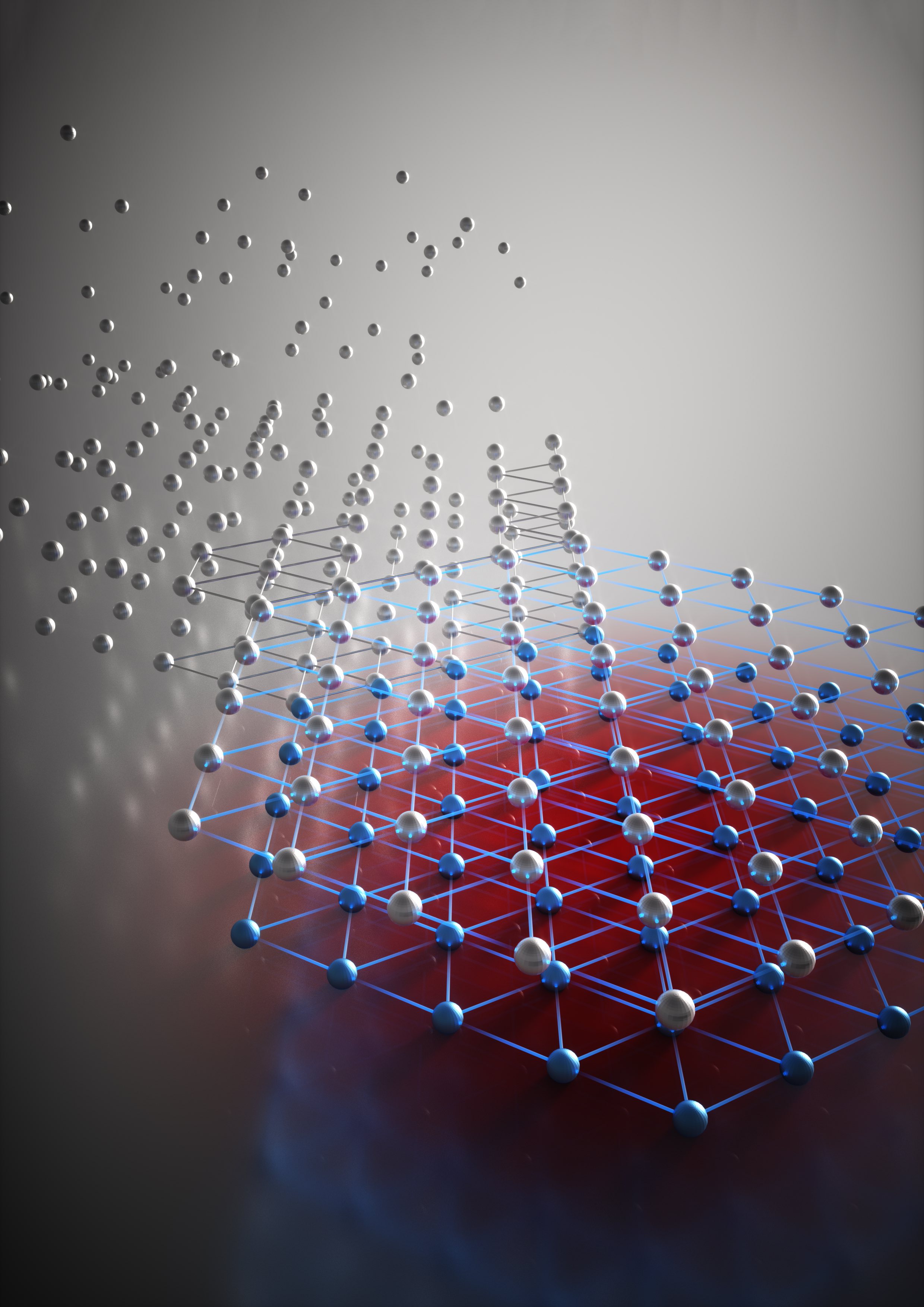

In 1934, physicist Eugene Wigner proposed a theory in quantum mechanics that for 87 years went unseen. The theory explained how a metal that normally conducts electricity could turn into a nonconducting insulator. Wigner theorized that when electrons in metals interact strongly and are brought to ultracold temperatures, these electrons would be frozen in their tracks and form a rigid, non-electricity conducting structure — a crystal — instead of zipping around at thousands of kilometers per second and creating an electric current. Since he predicted it, the structure was coined a Wigner Crystal and was observed for the first time in 1979. What’s remained stubbornly elusive to physicists, however, has been the melting of the crystal state into a liquid in response to quantum fluctuations. Now, almost 90 years later, a multi-institutional international team of physicists has finally experimentally documented this transition. The work is described in a new study published in Nature and marks a big step toward creating a system for studying these kinds of transitions between states of matter at the quantum level, a long-sought-after goal in the field. You Zhou, a materials science and engineering assistant professor at the University of Maryland (UMD), served as first author on the study while working as a post-doc at Harvard University. "This study opens up exciting avenues for investigating many previously predicted exotic electron states near the phase transition that were difficult to study," said Zhou. "We may even start to think about making novel quantum electronic devices based on Wigner crystals and their quantum phase transition." The research team, led by Harvard Professors Hongkun Park and Eugene Demler, focused on observing Wigner crystals and their phase transitions, which happen when a substance changes from a solid, liquid, or gas to a different state. When quantum fluctuations near absolute zero temperature drive these transitions, they are called quantum phase transitions and are thought to play an important role in many quantum systems. In the case of a Wigner crystal, the crystal-to-liquid transition happens from a competition between the classical and quantum aspects of the electrons – the former dominating in the solid phase, in which electrons are "particle-like," and the latter dominating in the liquid, in which electrons are "wave-like." For a single electron, quantum mechanics tells us that the particle and wave nature are complementary. "It is striking that, in a system of many interacting electrons, these different behaviors manifest in distinct phases of matter," said Park. "For these reasons, the nature of the electron solid-liquid transition has drawn tremendous theoretical and experimental interest." You Zhou, Jiho Sung and Elise Brutschea developed a novel experimental technique to observe this solid to liquid transition in atomically thin semiconductor bilayers. In general, Wigner crystallization requires very low electron density, making its experimental realization a major experimental challenge. By constructing two interacting electron layers from two atomically thin semiconductors, experimentalists created a situation in which the crystallization is stabilized at higher densities. To see the transition, the researchers used a method called exciton spectroscopy. They use light to excite an electron in the system and bind it to the electron vacancy, or hole, it leaves behind, forming hydrogen-like electron-hole pair known as an exciton. This pair interacts with the other electrons in the material and modifies its properties so they can be optically seen. "Usually, studying the electronic properties of these atomically thin nanostructures is challenging because making good electrical contacts and probing electron motion turns out to be extremely difficult," said You Zhou. The findings from the paper were largely accidental and came as a surprise, according to the researchers, however, they plan on using this new method to continue to investigate other quantum phase transitions. "The crystal themselves have been seen, but this, sort of, pristine transition — when quantum mechanics and classical interactions are competing with each other — has not been seen," said Demler. "It has taken 87 years." This research was conducted through a multi-disciplinary collaboration with research teams at UMD, Harvard University, Clemson University, National Institute for Materials Science in Japan, and Budapest University of Technology and Economics in Hungary. *Adapted with permission from a Harvard University article written by Juan Siliezar.

Related Articles: June 29, 2021 Prev Next |